Four Indigenous Philosophies to Help us Connect to Nature

We can learn a lot from indigenous worldviews on how to live harmoniously with Nature.

Inspired by our ReWild Yourself Champion, Tatiana Lopez, we dipped our toes in these rich waters and present four philosophies from indigenous peoples to help us better connect to Nature.

As part of our spotlight on Tatiana Lopez, one of our ReWild Yourself Champions, Class of 2024, we sat down for a wonderful wide ranging conversation earlier this month (check it out here).

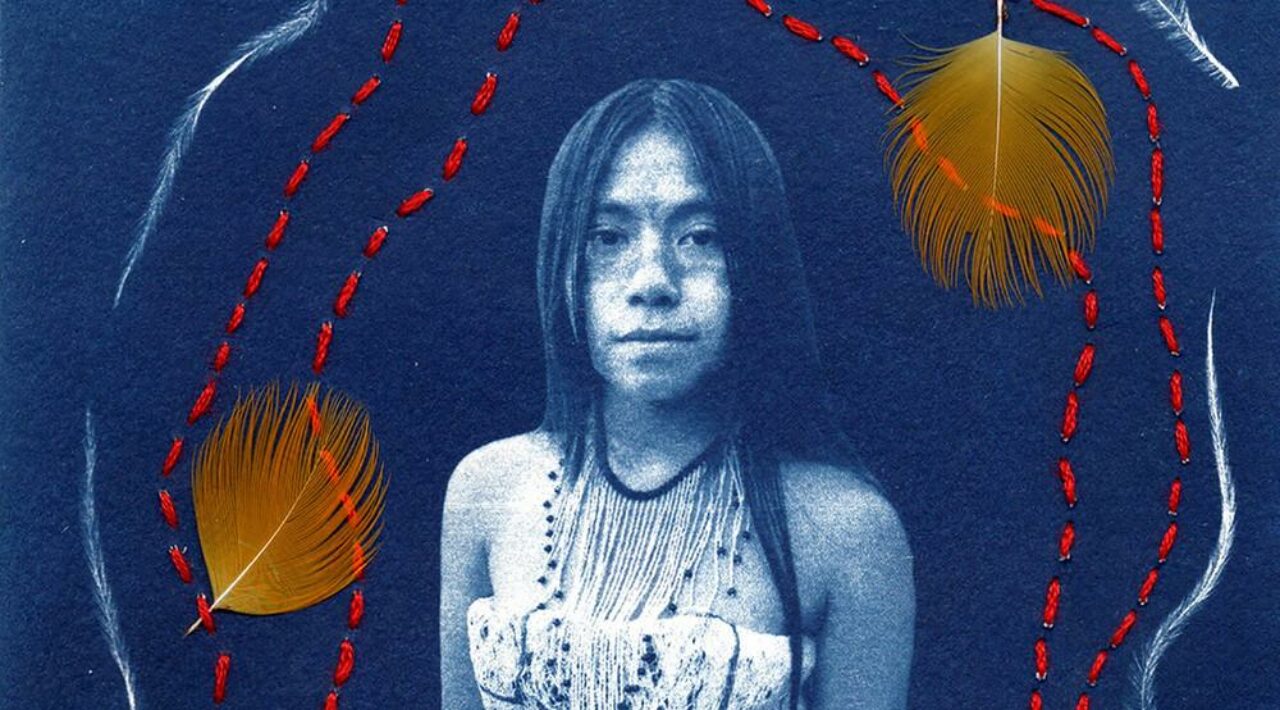

Something that really stuck with us was Tatiana’s account of time living with the Sapara in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Their ideas around Nature, spirits, and the subconscious – embodied by ancestral teachings of ‘witsa ikichanu’ (good living) – guides their sustainable relationship with the land, one built on tenets of reciprocity and gratitude.

Disclaimer

I am not an Indigenous person and understand that there is a history of extraction (resources, labour and now ideas), ethnocentrism, generalisation, romanticisation and misrepresentation when reporting on these groups. I will do my best to avoid these wrongs, but as a result of my ignorance and lack of direct cultural experience, will almost certainly fall short. That said, I have approached the article with respect and care.

Restoring the Kinship Worldview

Before delving into our four chosen philosophies, I wanted to share with you a wonderful book I have in my collection, which is highly relevant.

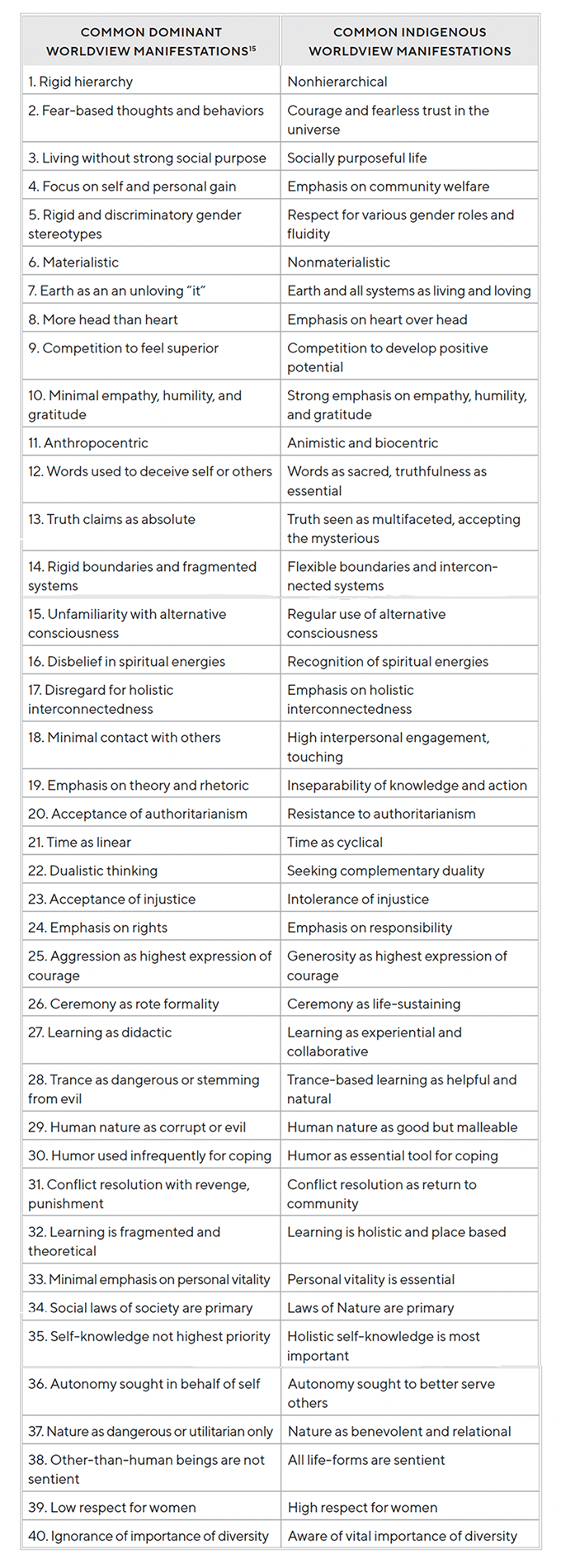

Wahinkpe and Darcia present 28 ideas and writings from Indigenous Voices, each with something to say on Rebalancing Life on Planet Earth. One of the most compelling parts of the book is a direct comparison between what they call the “Common Dominant Worldview”, which could be thought of as a modernised or Western view, and the “Common Indigenous Worldview”.

I have included the full table of the 40 points of comparison at the bottom of this article, taken from the book, but include below a number of ideas that seemed most relevant when considering the difference between our relationships with Nature. On the left is the “Common Dominant Worldview” most of you will be familiar with, with the “Common Indigenous Worldview”

- Materialistic Vs Non materialistic

- Earth as an unloving ‘it’ Vs Earth and all systems as living and loving

- More head than heart Vs Emphasis on heart over head

- Anthropocentric Vs Animistic and biocentric

- Disbelief in spiritual energies Vs Recognition of spiritual energies

- Disregard for holistic interconnectedness Vs Emphasis on holistic interconnectedness

- Emphasis on rights Vs Emphasis on responsibility

- Ceremony as rote formality Vs Ceremony as life-sustaining

- Nature as dangerous or utilitarian only Vs Nature as benevolent and relational

- Other-than-human beings are not sentient Vs All life-forms are sentient

To simplify, Western cultures tend to adopt an‘ ego’ rather than ‘eco’ approach to Nature. In place of restraint and balance, we are more likely to view Nature as a commodity and freely and carelessly impose our dominion over it.

Four philosophies from indigenous peoples to help us connect to Nature

Witsa ikichanu (good living)

When Tatiana was living with the Sapara, an indigenous people native to the Amazon rainforest along the border of Ecuador and Peru, the women she interviewed regularly discussed the importance of maintaining a ‘witsa ikichanu’, which has been translated to a ‘good life’.

Tatiana explains that witsa ikichanu is about protecting the energies of the forest, river and wind, and maintaining an open connection to the spirit world through dreams. It is about connection to place and creating and maintaining an inextricable link to the natural environment in which you live. This link helps them construct their identities and understanding of the world and also governs their interaction with the forest, based on reciprocity.

Place is important, not only in the construction of their identities and their understanding of the world, but also in their everyday interaction with the forest. Such a connection is hard for us to understand, perhaps impossible without some sort of spiritual element, but that search for a meaningful connection with the land is perhaps something we can find our own way to discover and practice.

Listen to Tatiana discuss what she learned from living with the Sapara in the video below.

Totems

The idea of Totems is similar to that of witsa ikichanu, and connecting to the spirit of the forest.

The difference however, is that Totems are more specific and personal: a familiar, tribal, or individual connection with a specific animal and its spirit.

They are common in Indigenous and Aboriginal Australian cultures, where an individual will inherit the symbol of a plant or an animal as a spiritual emblem. A person might have several totems, one for their tribe, another they share with their family, and then an individual Totem specific to them. Each totem represents a mystical relationship with the spirit of that animal. Not only does it engender a connection to the species, but also guides the person’s ‘real world’ interaction with that species. A person with a kangaroo as a totem for example, would be expected to serve as a champion, representative and protector of kangaroos, and would also never hunt one. This has a very practical effect of reducing the chance of over exploiting any one resource, as there is always part of the population who will not use it.

Many other indigenous groups, such as several Native American tribes, have worldviews that facilitate similar personal relationships with specific species, often established through ritual, vision quests, or dreams.

Personally, the idea of totems reminds me of my time working at the Natural History Museum with the scientists there: specialists and champions of specific groups of plants and animals. Each equally as passionate about their own species, and as a result holding valuable information on how best to protect it. If each of us had such a connection, championing our own special species, the tree of life would have a protector for every branch and twig.

Watch the video below from the University of Sydney to find out more about Aboriginal Totems.

‘Kaitiakitanga’ – guardianship

‘Kaitiakitanga’ is an ancient Maori concept of guardianship and management of the environment. As with the other indigenous philosophies mentioned so far, it manifests from a deep kinship between humans and the natural world.

It follows that a deep connection to Nature leads to strong feelings of care and concern, which then engenders a desire to protect; this is ‘Kaitiakitanga’. A Kaitiaki is a person or group given a specific guardianship role by the iwi (“tribe”) over a specific area, such as a lake or forest.

We might make the equivalence of a “ranger” or “warden”, but the key distinction is the depth of responsibility felt. The Kaitiaki are protecting and guarding the environment as it is seen as an extension of themselves, their families and communities. The responsibility is also about respecting their ancestors as well as securing a future for the generations that follow. Although this feeling and philosophy is shared by many non-indigenous people, without the spiritual belief embedded in a culture, the strength of connection is hard to create.

A lot of ‘Kaitiakitanga’ is about sustainable management of resources, being mindful of the timings of harvest, the quantity and frequency of hunting and foraging, and about careful observation and monitoring of the environment. This leads us on to the fourth and final of our philosophies, that of the ‘Honourable Harvest’.

The Honourable Harvest

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Citizen of the Potawotomi Nation, describes the Honourable Harvest in her wonderful book Braiding Sweetgrass, and introduces it as “the Indigenous canon of principles and practices that govern the exchange of life for life”.

In essence, it is a set of rules based on thousands of years of harmonious living, which protects against practices that compromise the life sustaining energy of mother Nature.

Once non-human beings are considered as kinfolk rather than objects, an honourable harvest becomes the only tenable option. Robin has collated a list that summarises these tenets, included below.

They all seem innately reasonable, yet consider how we regularly break these rules (often obliviously) as individuals or as part of systems where we are disconnected from the impacts of our actions on Nature.

The Honourable Harvest

- Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them.

- Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life.

- Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer.

- Never take the first. Never take the last.

- Take only what you need.

- Take only that which is given.

- Never take more than half. Leave some for others.

- Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

- Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken.

- Share.

- Give thanks for what you have been given.

- Give a gift in reciprocity, for what you have taken.

- Sustain the ones who sustain you and the word will last forever.

A final thought

Without growing up amongst the communities mentioned above, sustained on the philosophies discussed, we can’t hope to fully comprehend or adopt them. Nor should we need to.

We are each part of our own cultures and heritage, rituals and habits – some of which include elements of witsa ikichanu, totems, Kaitiakitanga and the Honourable Harvest – and it would be wrong and impossible to abandon them. However, modernity has left us running out of road. We would be foolish not to learn from those with a long history of living harmoniously with nature, to find ways to weave these various philosophies of reciprocity, gratitude and kinship into our own stories. I would love to hear people’s thoughts on how best to do this…

Table showing Dominant v indigenous worldview. From ‘ Restoring the Kinship Worldview – by Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows) and Darcia Narvarez, PHD’

Dominant v indigenous worldview. From ‘ Restoring the Kinship Worldview – by Wahinkpe Topa (Four Arrows) and Darcia Narvarez, PHD’

Join Our Community...

Sign up for stories, tips and inspiration from around the globe.