Calling for a “Right to Roam”

When we first met up with Sam Lee, one of our ReWild Yourself Champions (class of 2024) one of the things we asked him was what he would change politically or culturally to improve people’s access and connection to Nature.

Without missing a beat, Sam said:

“Well the big thing for me would be a Right to Roam Act. Or should I say, to extend the “Right to Roam” in Scotland to the rest of the UK. A permissive attitude towards people walking in Nature, not confined to footpaths, access to rivers, all within criteria of respect and adherence, to protecting farmer’s crops and people’s privacy, but particularly access to forests and rivers.”

Another of our Champions, Nicola Chester, also had this to say,

“I am also a big advocate for the “Right to Roam.” I’m a great believer in access to Nature for all; of a responsible, codified, invested right to connect to the land. We cannot expect people to care for Nature if it is inaccessible to them – that by implication and long cultural practice, isn’t for them to worry or care about, or indeed get involved in or be responsible for. Community is one of the most powerful and radical instincts we have as a species. And that includes us as part of Nature, and Nature as part of us, wherever we live. This is the community and connection we owe our existence and joy to, and access is key.”

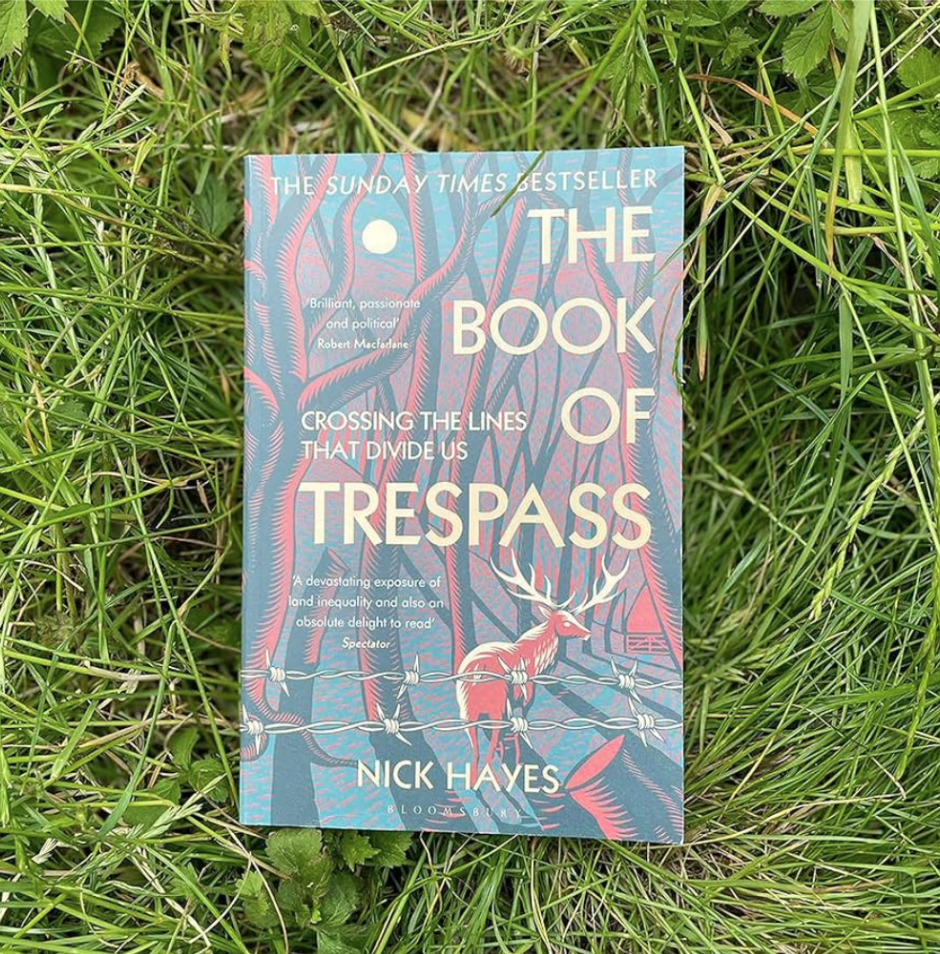

In fact, both Sam and Nicola have written on the Right to Roam as their contributions to the upcoming Nature connection book, Wild Service (curated by Nick Hayes), out April 25th this year.

So, what is a “Right to Roam”, and why could it be so important? Ahead of the release of Wild Service, we thought we’d break things down to some of the basics.

What is a “Right to Roam”?

A “Right to Roam” is an ancient custom that allows anyone to wander in open countryside, no matter who owns it. Currently, in England and Wales, the public have the right to walk and access fairly restricted parts of the land, largely keeping to public rights of way, as outlined in the Countryside Rights of Way Act of 2000.

In Scotland however, the situation is different. The Scottish government introduced the Land Reform (Scotland) Act in 2003, which gives the public a legal right to access most land and waterways, provided they act responsibly. There are a few exceptions, including gardens and land with crops, but otherwise, people in Scotland can essentially go wherever they wish. It is this access to the land that people are calling for for the rest of the UK.

The “Right to Roam” campaign

In 2020, Illustrator, author and activist Nick Hayes wrote the fabulous Book of Trespass, an exploration of access and ownership of the land and a radical call to reject the meager entitlement we are currently permitted. It tapped into an undercurrent of dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs and ignited a spark.

Building on this interest and momentum, and an emerging “alliance of ramblers, wild swimmers, paddle-boarders, kayakers, authors, artists and activists,” Nick partnered with environmental campaigner and author Guy Shrubsole, to create the Right to Roam campaign, with a clear mission:

“To bring a Right to Roam Act to England so that millions more people can have easy access to open space, and the physical, mental and spiritual health benefits that it brings.”

If you are interested in finding out more or joining the campaign, visit www.righttoroam.org.uk.

The campaign has already had some success, and was instrumental in the 2023 protests on Dartmoor, helping influence the reversal of the High Court’s decision in the case of Darwall v Dartmoor National Park Authority. The result meant that wild camping is now permitted (with a few exceptions) on Dartmoor Commons without requiring the landowner’s permission.

How much access do we currently have to the land?

The Countryside Land and Business Association estimates that more than 140 000 miles of footpaths are available to the public, and more than 500 000 hectares of woodland are open for the public to access. This sounds like an awful lot, but the Right to Roam campaign suggests that only 8% of England is open to the public, with more than 92% of the countryside, and 97% of rivers off limits.

Whether that seems right or not depends on your views on land ownership and whether the natural environment, and the various benefits it provides, is something that should be partitioned off and distributed based on various privileges.

Why does it matter?

Ultimately, it comes down to connection to Nature, or more specifically disconnection from Nature. When we are excluded from so much of the land, and where we have culturally accepted this idea of exclusion, then we don’t even see or experience so much of the wonderful nature we have on these wild isles. We also don’t have access to those full benefits for our physical and mental health, don’t properly notice the decimation of Nature that is occuring, and don’t care with the sort of urgency we should.

As scientist Robert Michael Pyle put: “People who care conserve; people who don’t know don’t care. What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never known the wren?”

A connection to Nature, established from a young age, and built into our habits, hobbies and culture, will help us care. A “Right to Roam and a right to reconnect to the land is a key part of the solution. Connected citizens become active advocates and protectors of Nature, we see that in places like Sheffield, where a community came together to protect trees on their streets (a story told brilliantly in The Felling documentary).

Beyond the Nature connection argument, for many the “right to roam” is an issue of principles, of what is right and fair. Many don’t dispute the idea of land ownership, but the right to exclude others from that land seems morally unjust. Nature and its benefits is not a commodity to be monopolised, but a right to all humans.

What is the argument against a “Right to Roam”

Those who are against a “Right to Roam” largely do so based on a lack of trust that the public would act responsibly in the wider landscape. They cite littering and dog attacks on livestock at an all-time high, and a public lack of understanding of Countryside Code that would lead to significant damage to wildlife and crops.

Farmers are already under enormous pressure to produce more with less, while also transitioning to more sustainable farming practices, so there should be clear sympathy, especially for those who have been impacted by irresponsible behaviour.

However, it seems short sighted and cynical to simply block off large swathes of the countryside as a result. In addition, the damage cited dwarfs in comparison to that caused by over extraction of resources, unchecked pollution, damaging industrialised farming, and the impacts of climate change, all enabled by the broken relationship many of us have with Nature. And without more access and connection to Nature, how will this culture and behaviour change?

The answer, according to the “Right to Roam” campaign, is to ensure reasonable and responsible behaviour, supported by better education and awareness of the Countryside Code, and by adhering to three key tenets:

Respect the interests of other people.

Care for the environment.

Take responsibility for your own actions.

What do the public think?

Well, that depends on who you ask! According to the Country Land and Business Association (CLA), and a poll carried out by Opinium in 2022, only 21% of people believed that a right to roam should be implemented in England. However, a survey of 2029 people conducted by YouGov on behalf of the Right to Roam campaign found that more than 60% of people in Britain support following in Scotland’s footsteps and introducing a right to roam in England. Make of that what you will!

What do you think? Is it a good idea or not? We would love to know, so get in touch and share your thoughts.

– By David Urry

Join Our Community...

Sign up for stories, tips and inspiration from around the globe.