Why folklore matters…

Last month we posted a short clip on Instagram from our interview with ReWild Yourself Champion, Lucy Ní hAodhagáin (O’Hagan). In it, Lucy discusses an initiative in 1930s Ireland to capture the country’s folklore before it was lost in time. We couldn’t believe the response we got, with thousands of likes and hundreds of comments, so David Urry decided to delve a little deeper…

The Schools’ Collection

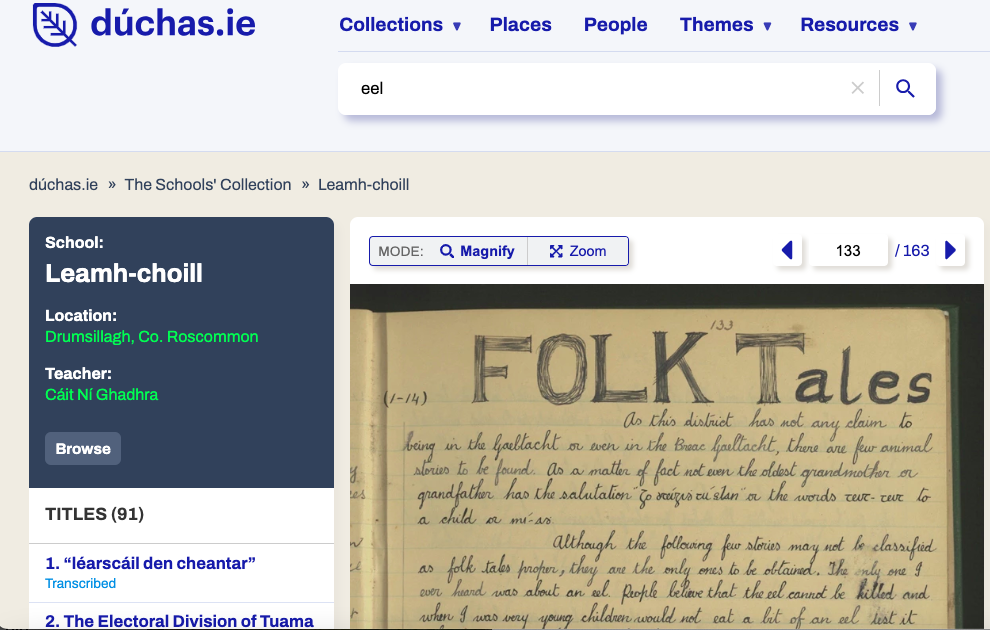

As Lucy mentioned in their interview (watch the clip below, or full conversation here), the then Taoiseach (Prime minister) of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, along with his wife, Sinéad Ní Fhlannagáin (a teacher folklorist and Celtic revivalist herself), strongly believed in the preservation of folklore. Under his watch, and the leadership of Séamus Ó Duilearga and Seán Ó Súilleabháin, the recently established Irish Folkore Commission devised the Schools Collection Scheme in 1937.

Crowdsourcing kids

The idea was beautifully simple, and an innovative use of homework! Primary teachers presented their older students with fresh notebooks and instructed them to collect and record from their parents, grandparents, aunts uncles etc…as many folk tales, myths, customs, and local history of the land as they could. It was an idea borrowed from a similar initiaive run in Sweden.

What came back was astonishing — a glorious piece of citizen social research and a snapshot of collective Irish lore. Around 50,000 students from 5000 schools took part over the course of two years. Every county of Ireland took part (save for the six disputed Northern counties). It amounted to almost three-quarters of a million pages of (mostly) exquisitely neat handwriting.

The resulting collection is known as the Schools’ Manuscript Collection 1937 – 1938 and is available in most county libraries around Ireland. Amazingly, you can also find it online. Following a colossal effort the collection has been digitized — freely available for anyone to delve into, along with millions of other documents from the National Folklore Collection, hosted at University College Dublin.

Jump in at www.https://www.duchas.ie

Why folklore matters

But why bother? What was it that Éamon de Valera, Sinéad Ní Fhlannagáin and those at the Irish Folklore Commission saw as so important, to launch initiatives such as the School’s Collection and capture and promote Irish lore? And why do people like Lucy and many others choose to continue to preserve and elevate such traditions and stories.

Preservation of culture, a connection to our past, and a sense of identity and belonging

Folklore can act as a live repository of cultural knowledge, beliefs, and practices as that are passed down through generations. In turn, this can create a sense of shared identity and community, of something bigger than ourselves — a connection to our past, our history and the land. Although stories may evolve and change over time, they offer a window into the past, how people lived and what they valued.

In Ireland, in the 1930s, this emphasis on national identity was particularly significant, as part of a cultural revitalisation following centuries of English dominance. This is often referred to as the “Gaelicization” policy, and folklore — along with a revival of the Irish language – were central to this. In the words of Éamon de Valera below, upholding these national totems are presented as a duty of the people of Ireland:

“We, of our time, have played our part in the perseverance, and we have pledged ourselves to the dead generations who have preserved intact for us this glorious heritage, that we, too, will strive to be faithful to the end, and pass on this tradition unblemished.” Éamon de Valera

A reminder how to be human

Some folk tales are wild and absurd, but many contain moral lessons, teaching values and behaviours associated with particular cultures. Stories are the best way we have to vicariously experience the world and different realities and situations, and when told well, they can powerfully communicate various moral, ethical or cultural wisdoms. They also provide reassurance in times of uncertainty, or reminders of previous moments of resilience, community spirit and fortitude.

In their interview, Lucy describes the cultural and ecological amnesia that we see today, where in some instances we seem to have “forgotten how to be human”. Much of the day-to-day realities of life and survival, such as feeding ourselves, or caring for each other, have been externalised, whether through technology, markets, or large-scale systems and operations. While this has brought numerous benefits, in many ways it has created a crutch, or even infantilised us as a species.

The best folk tales speak to a constant humanity and remain eternally relevant. They help us re-connect to our more basic human strengths and qualities, giving us an extra layer of resilience and self sufficiency in the face of crisis, be it social, climate, or ecological.

Creativity and expression

The often magical or supernatural nature of folklore provides wonderful fodder for the imagination, art and creativity. Nobody owns folklore, which means there is constant space for self expression, reinterpretations, retellings, and creative responses, allowing individuals to engage with their culture and heritage in meaningful, personal and imaginative ways.

Environmental awareness and a connection to Nature

Perhaps the most valuable impact of folklore (and the one we are most interested in!) is its ability to connect us to Nature. In their interview, Lucy describes the way that our attention has been coopted by technology, constant communication, and consumerism. That part of us which was previously used to identify animal tracks or food to forage, is instead now utilised to identify a multitude of brands and logos, or to navigate screens and operating systems. This cooption of our attention has contributed to our disconnection with Nature.

Folklore is full of stories of the land and wildlife, because this was what used to fill our attention, and upon which we relied. As a result, an immersion in folklore is an excellent antidote to Nature disconnection, it reminds us how we intersect with the more-than-human world, both practically and on a more spiritual level. We can also select or adapt folk tales to specifically speak to our current ecological context and crises, which have invariably shifted enormously. Folklorists, like

More folk collections

Ireland isn’t the only place to have attempted to gather and preserve its folk heritage and make them available digitally. Why not visit the following databases:

Sagnagrunnur — visit

Folk legends and wonder tales from Iceland, the Faroes, Orkney and Shetland: published legends and sound recordings.

Sägenkartan — visit

Legends from Sweden and Norway

The Danish Folklore Nexus — visit

Legends from Denmark

SAMLA — visit

Norwegian digital folklore archive

Tobar an Dualchais (Kist o Riches) — visit

Sound recordings of Scottish folk legends and wonder tales: School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh.

Duchas — visit

Digitised Irish folklore

Folklore is YOUR lore — but it only persists in the retelling, and that is down to us

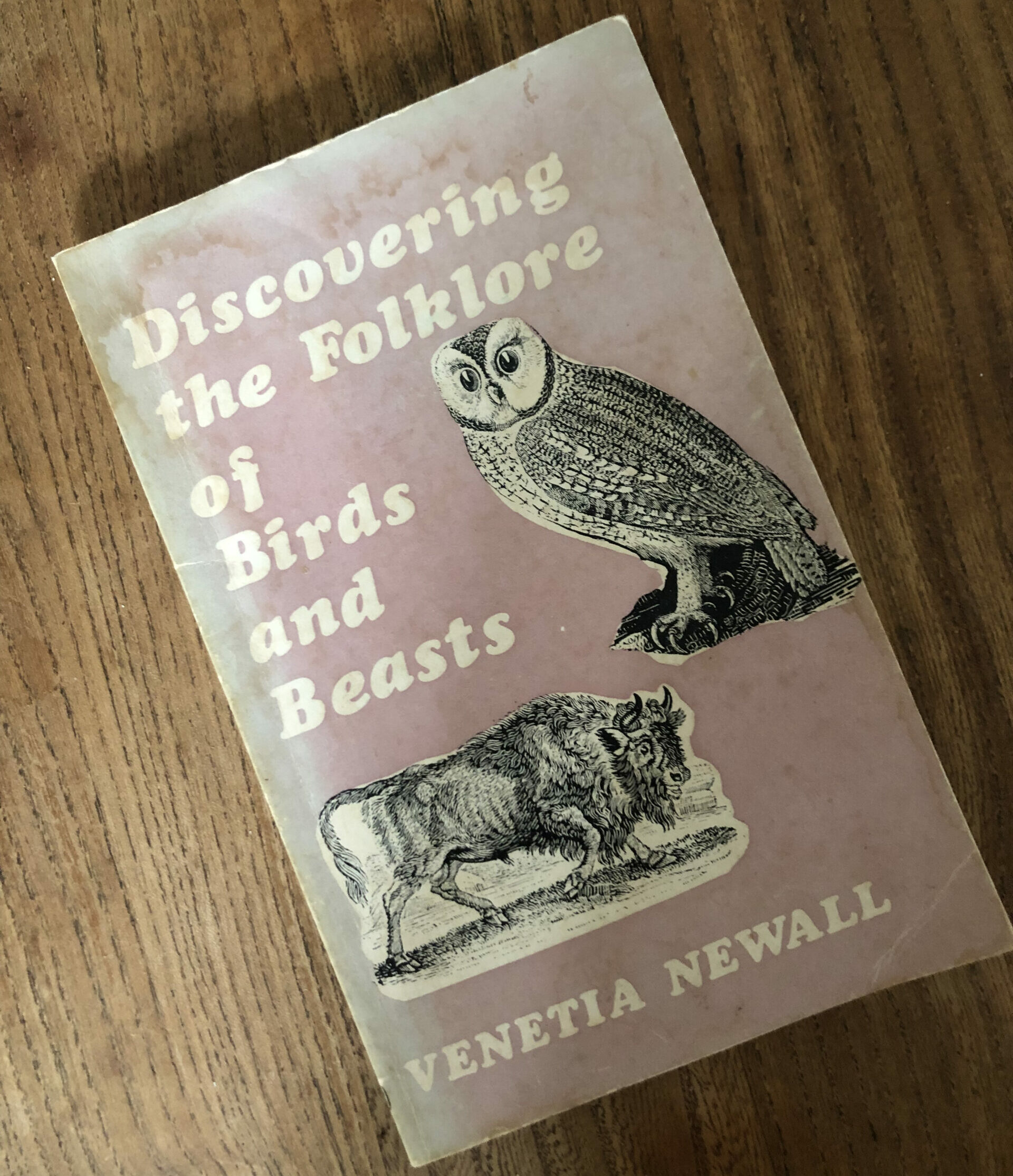

I also recommend raiding charity shops and your local book store. You can find some real treats and there is nothing better than leafing through a book and sinking in to a ripping yarn! Below are a few from my own collection.

More from ReWild Yourself Champion Lucy Ní hAodhagáin (O’Hagan)

Join Our Community...

Sign up for stories, tips and inspiration from around the globe.